PROTOTYPES MADE FROM LEGOS (Page 1 of 3)

These photos show a prototype module, basic articulation capabilities, and connections between two modules.

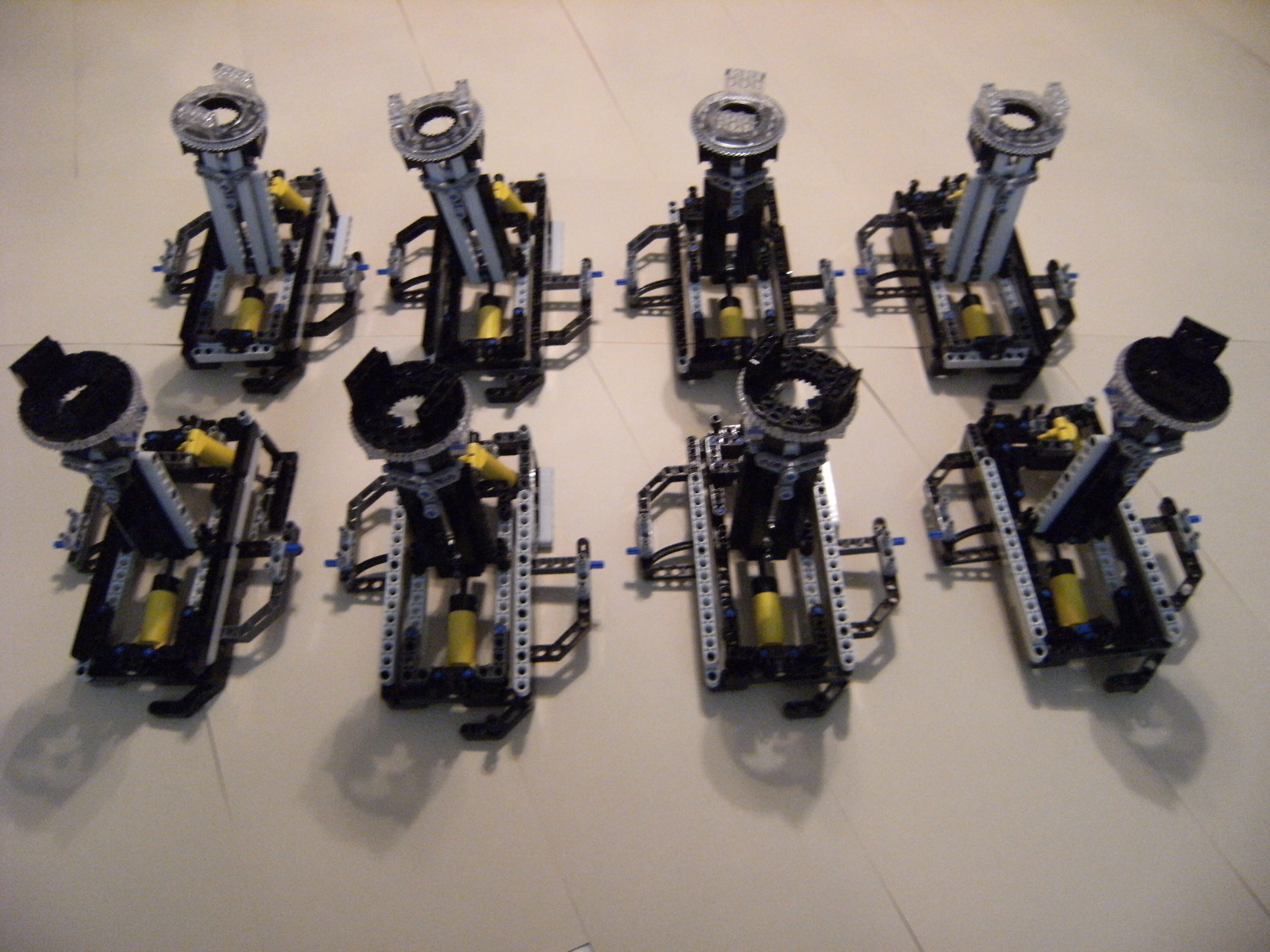

Supply of 6 modules

Supply of 6 modules

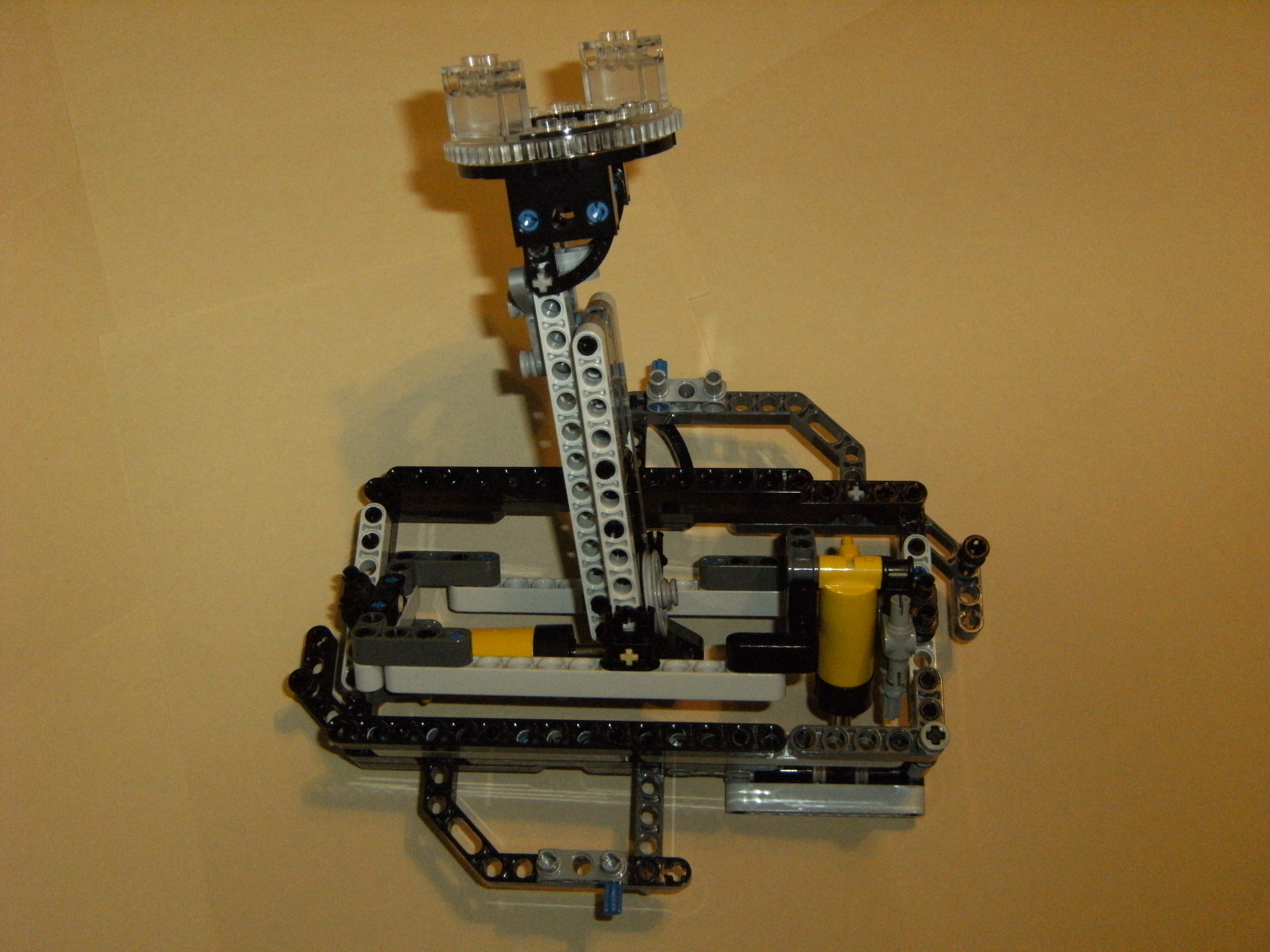

Figure 1. Side view Supply of 6 modules

Supply of 6 modules

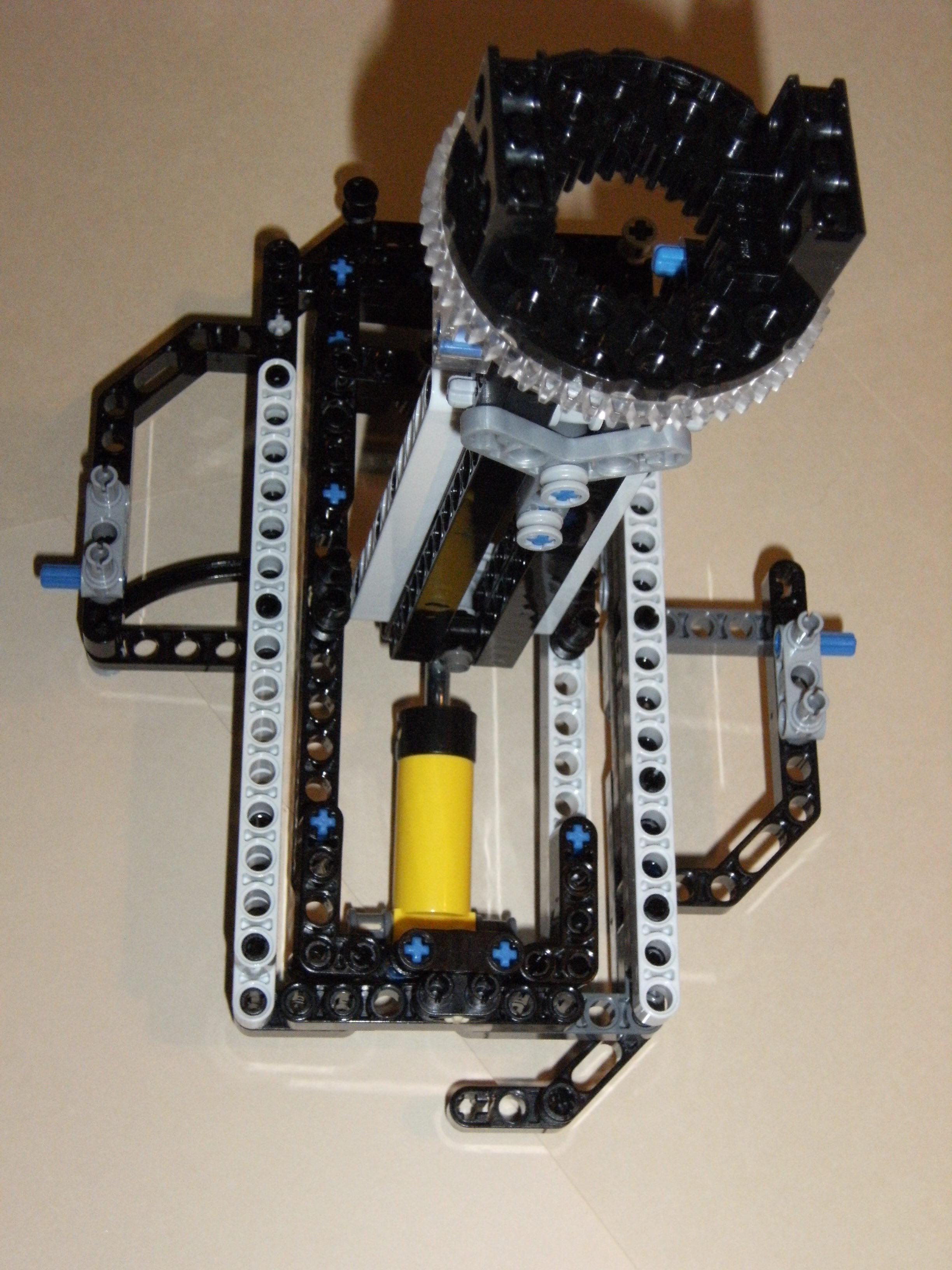

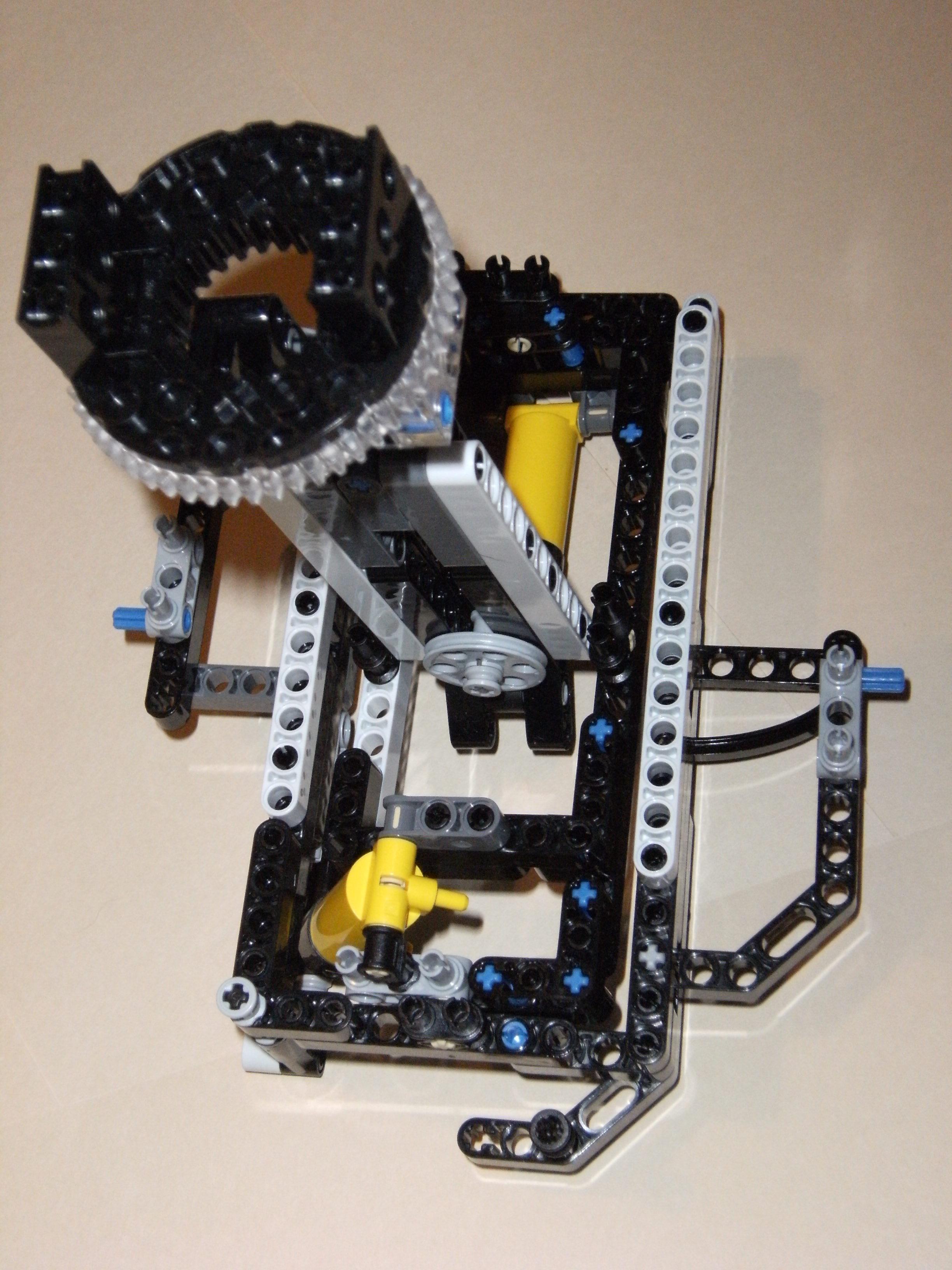

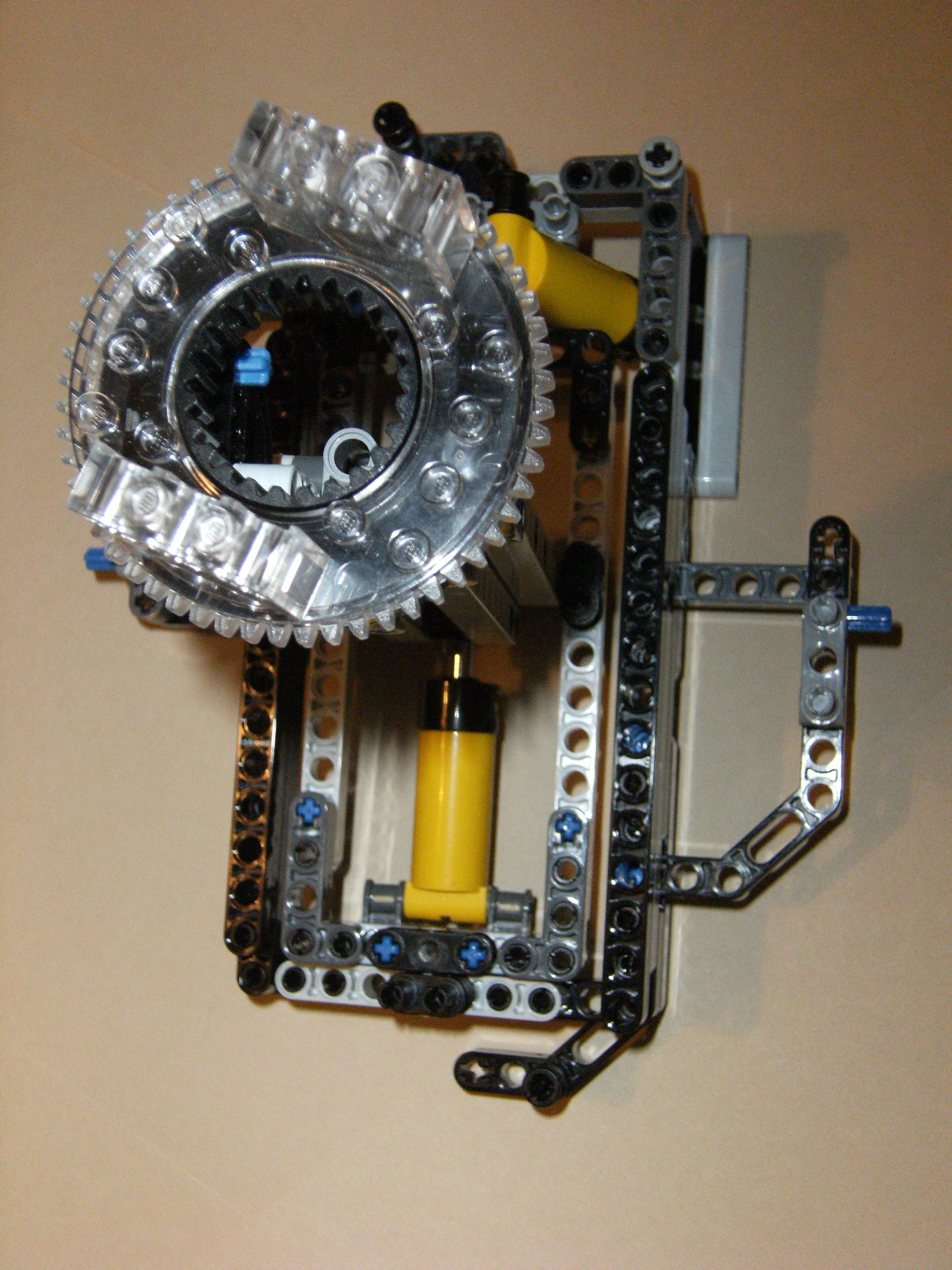

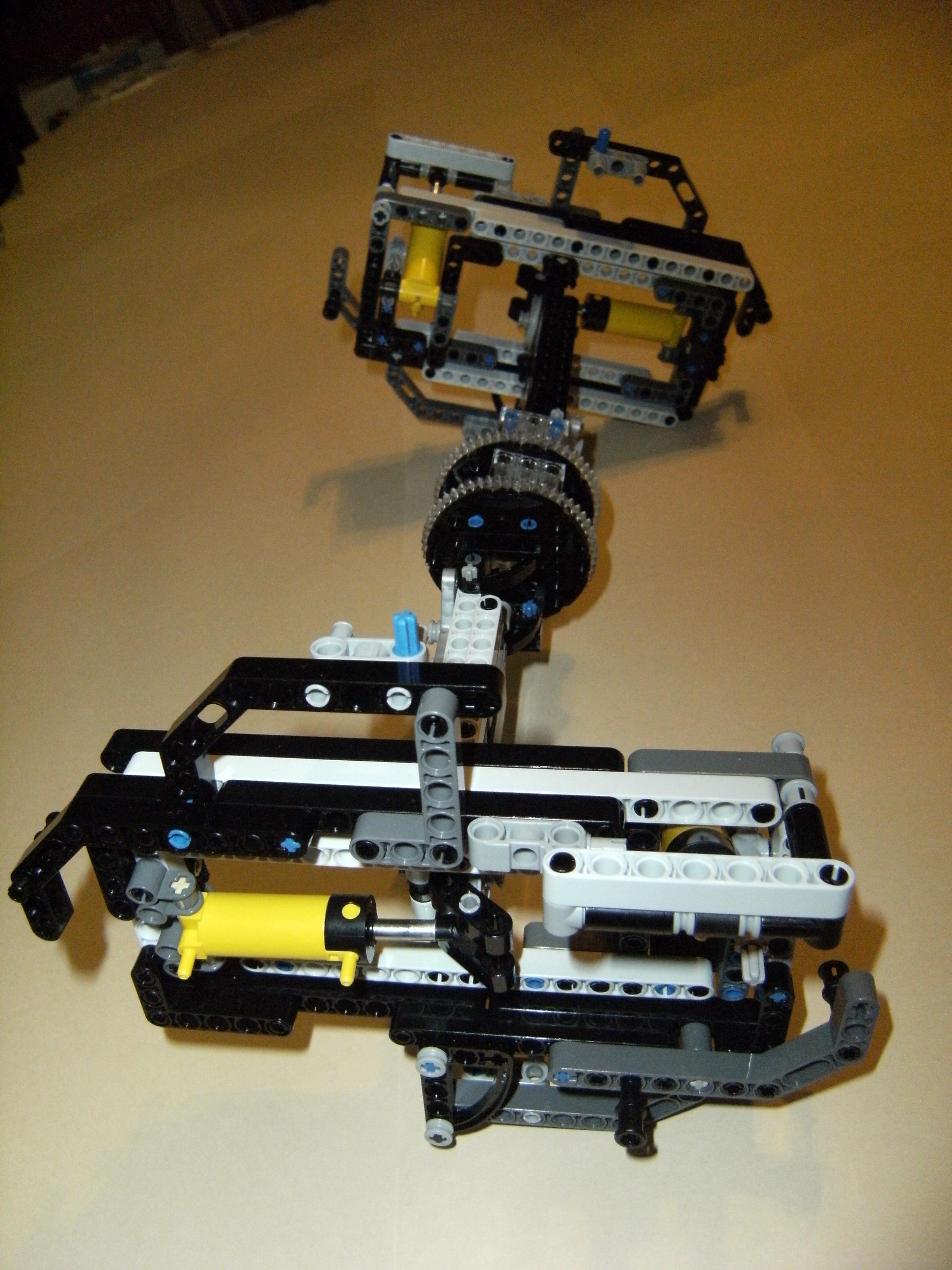

Figure 2. Top view Module prototype with inverted Lego turntable

Module prototype with inverted Lego turntable

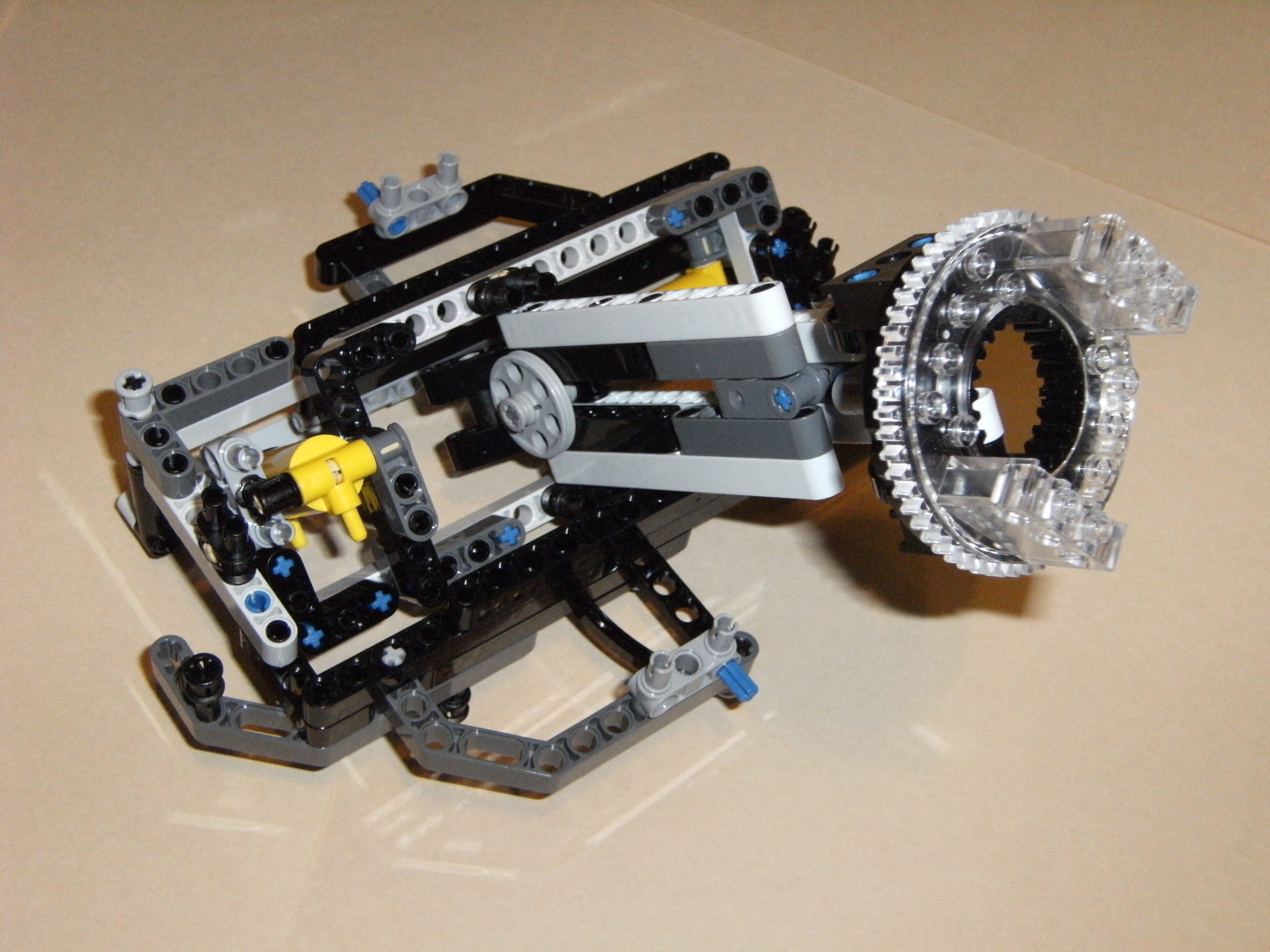

Figure 3. View 1 Module prototype with inverted Lego turntable

Module prototype with inverted Lego turntable

Figure 4. View 2 Module prototype with inverted Lego turntable

Module prototype with inverted Lego turntable

Figure 5. View 3 Module prototype with inverted Lego turntable

Module prototype with inverted Lego turntable

Figure 6. View 4 Module prototype with inverted Lego turntable

Module prototype with inverted Lego turntable

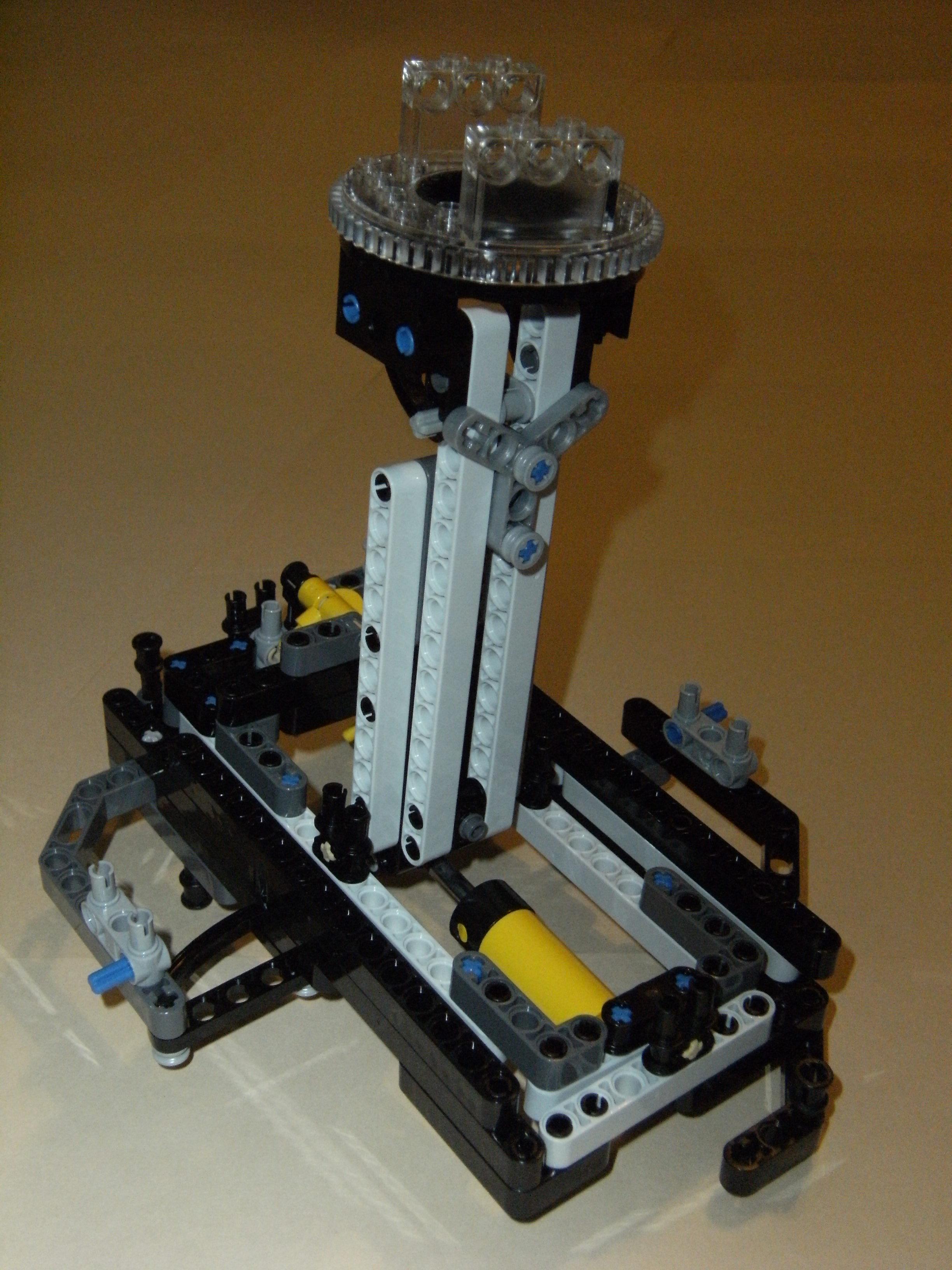

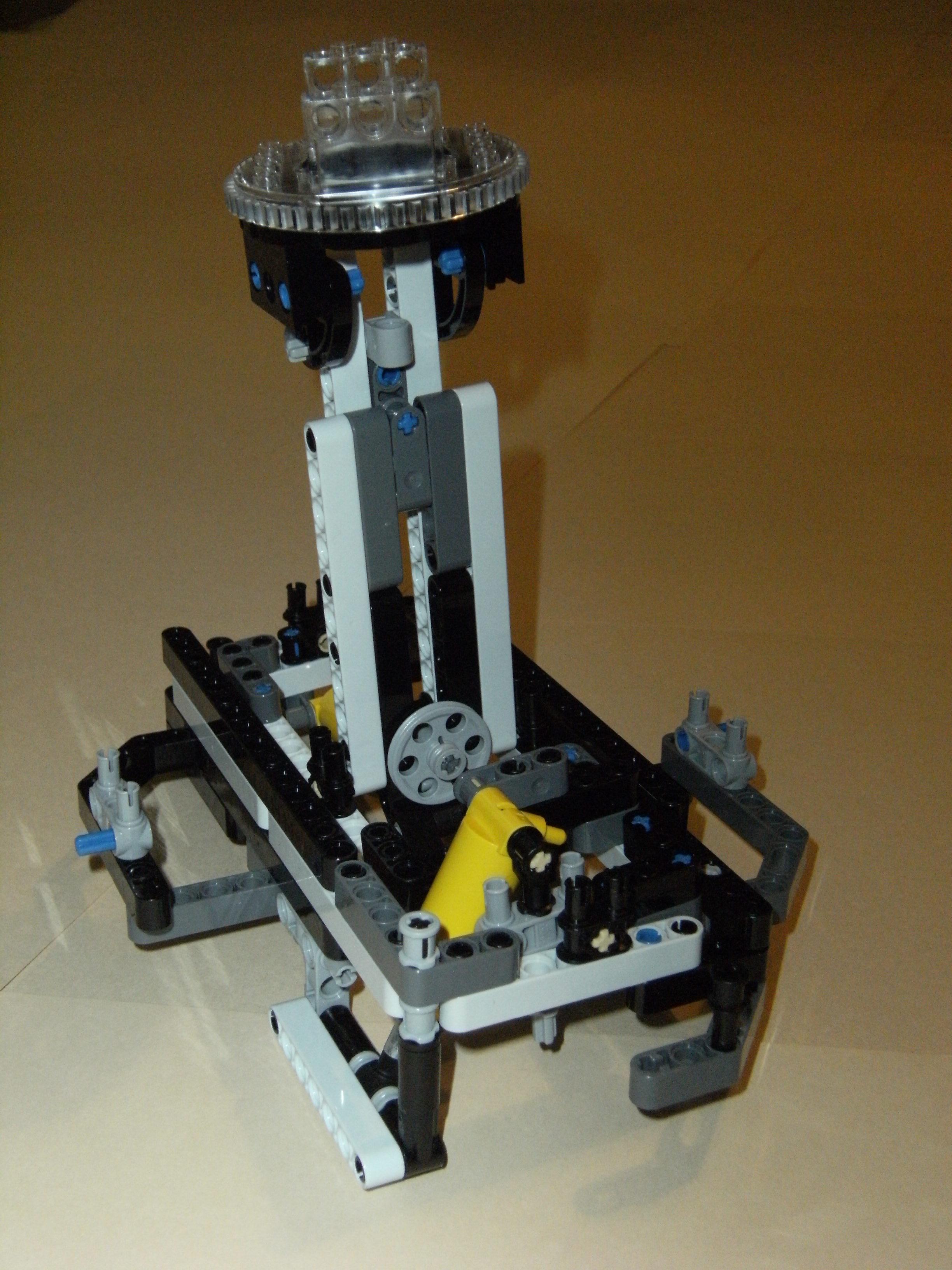

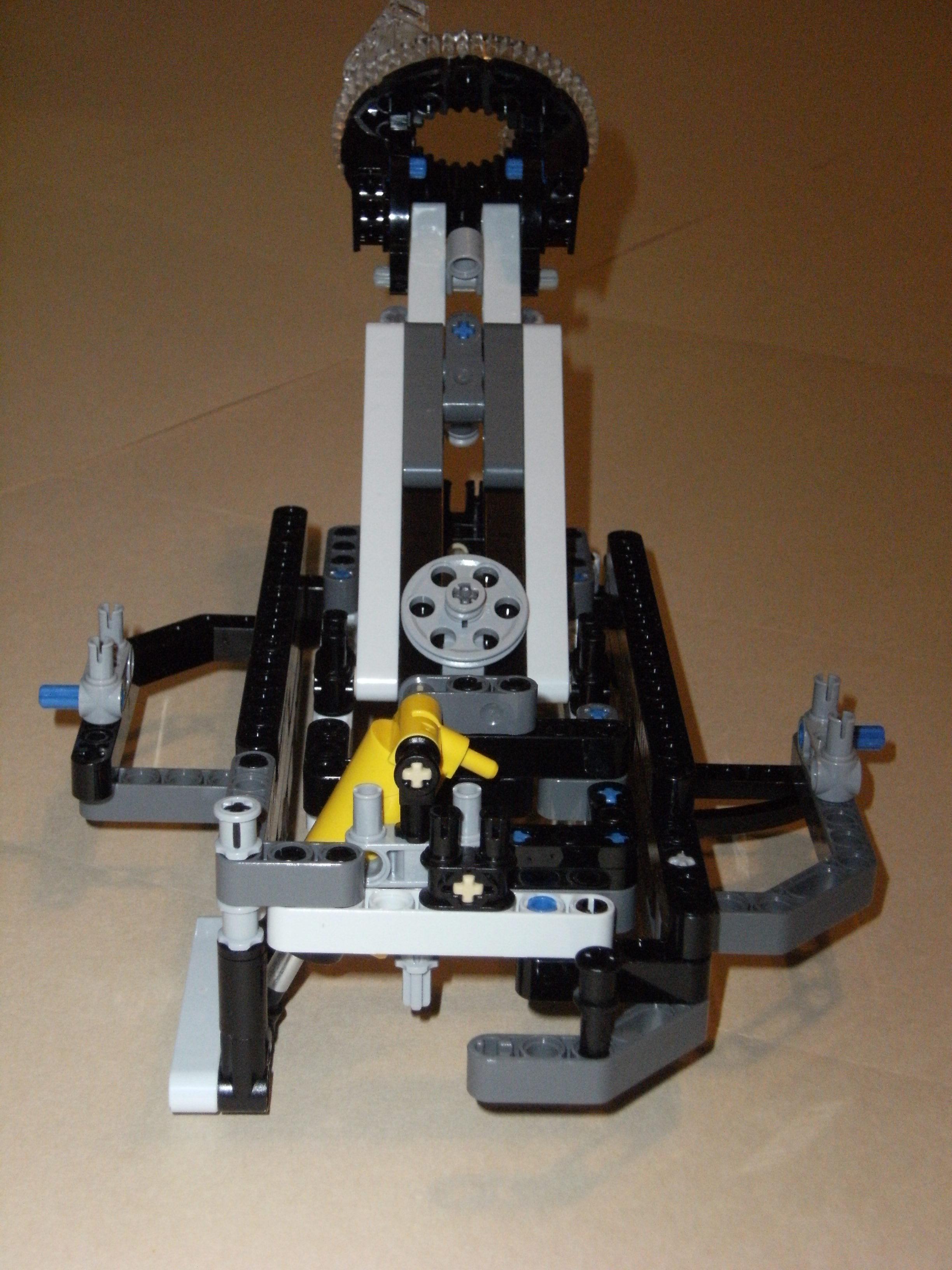

Figure 7. View 5 Module prototype with right-side-up Lego turntable

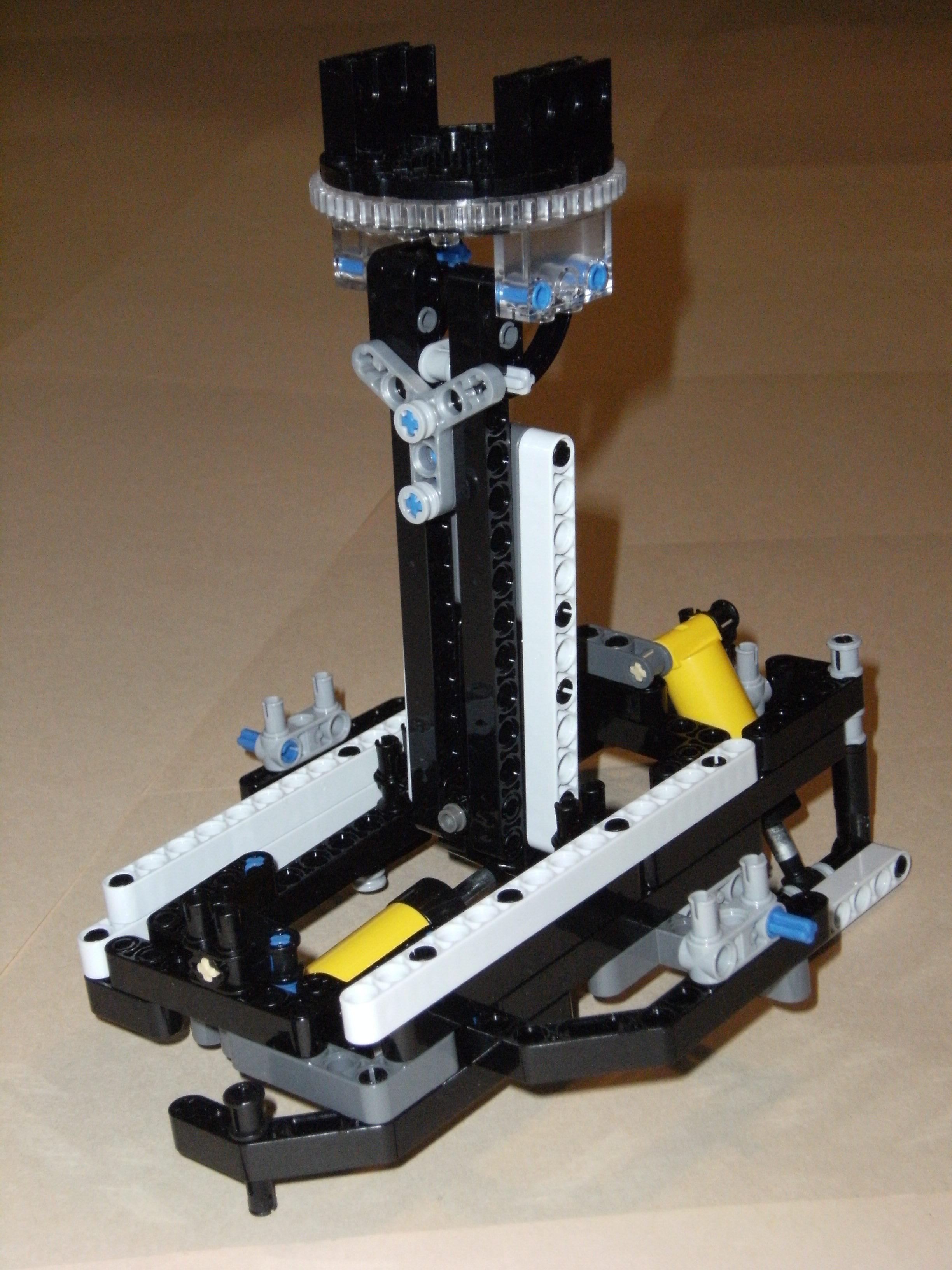

Module prototype with right-side-up Lego turntable

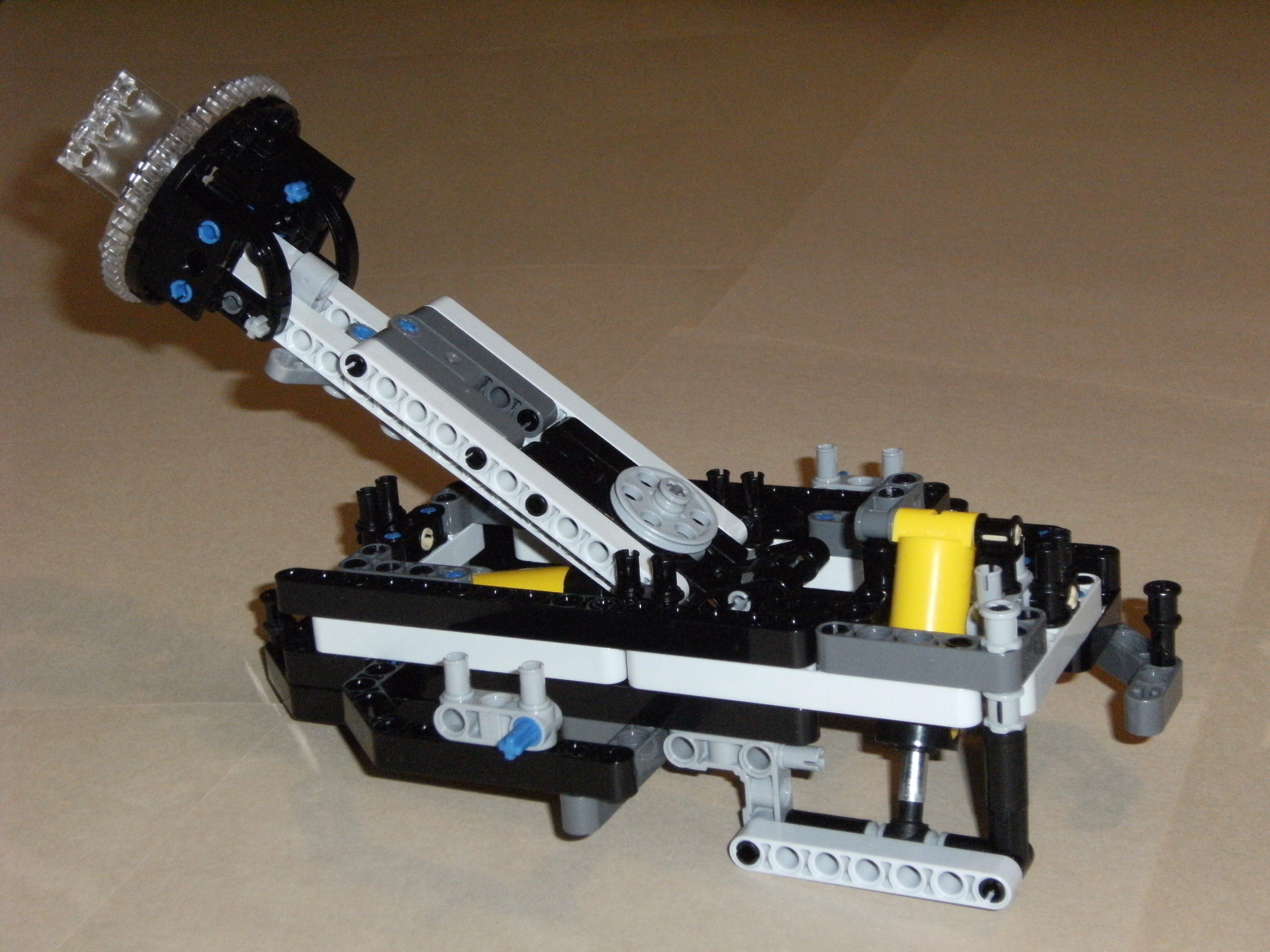

Figure 8. View 1 Module prototype with right-side-up Lego turntable

Module prototype with right-side-up Lego turntable

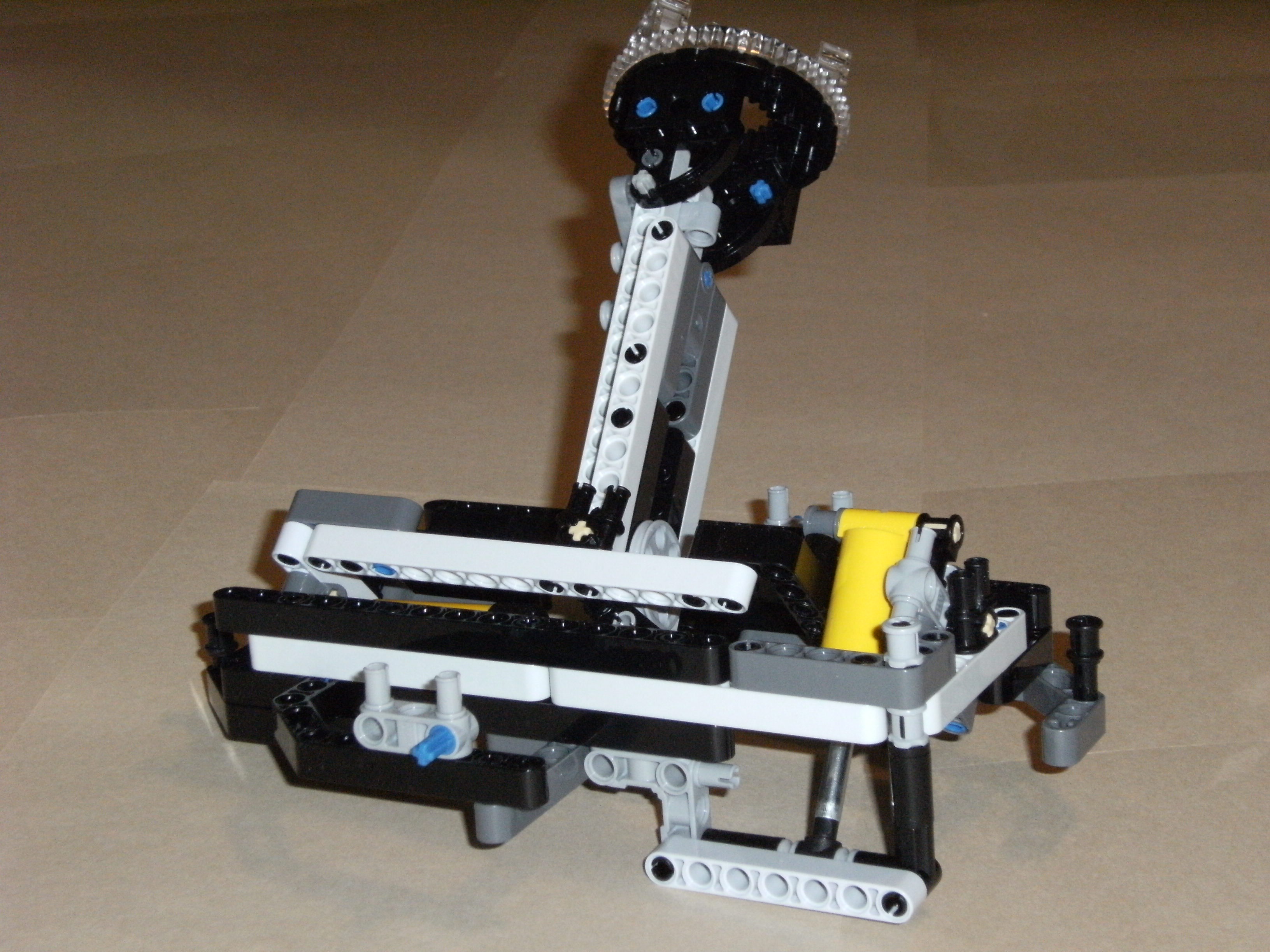

Figure 9. View 2 Module prototype with right-side-up Lego turntable

Module prototype with right-side-up Lego turntable

Figure 10. View 3 Module prototype with right-side-up Lego turntable

Module prototype with right-side-up Lego turntable

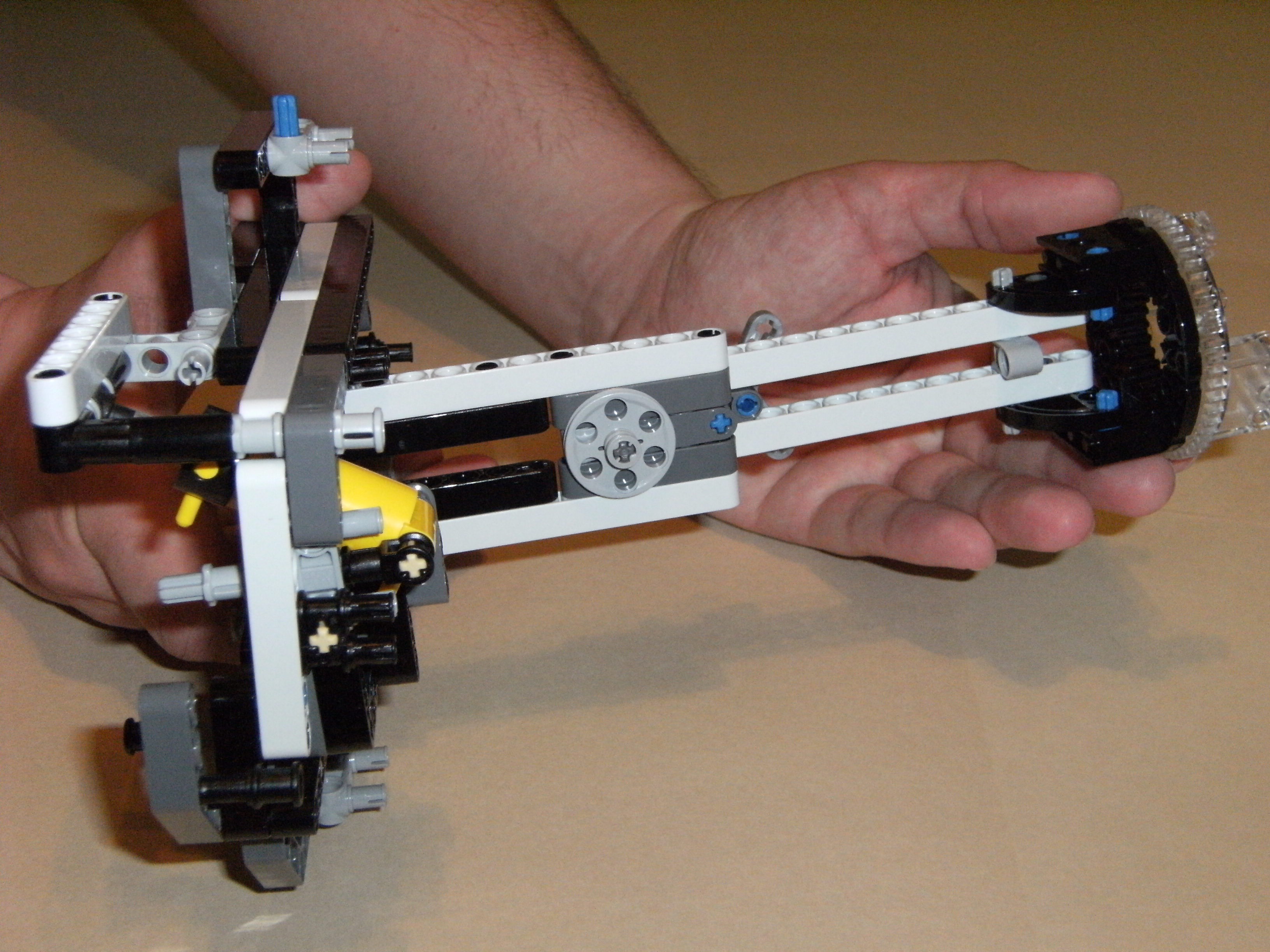

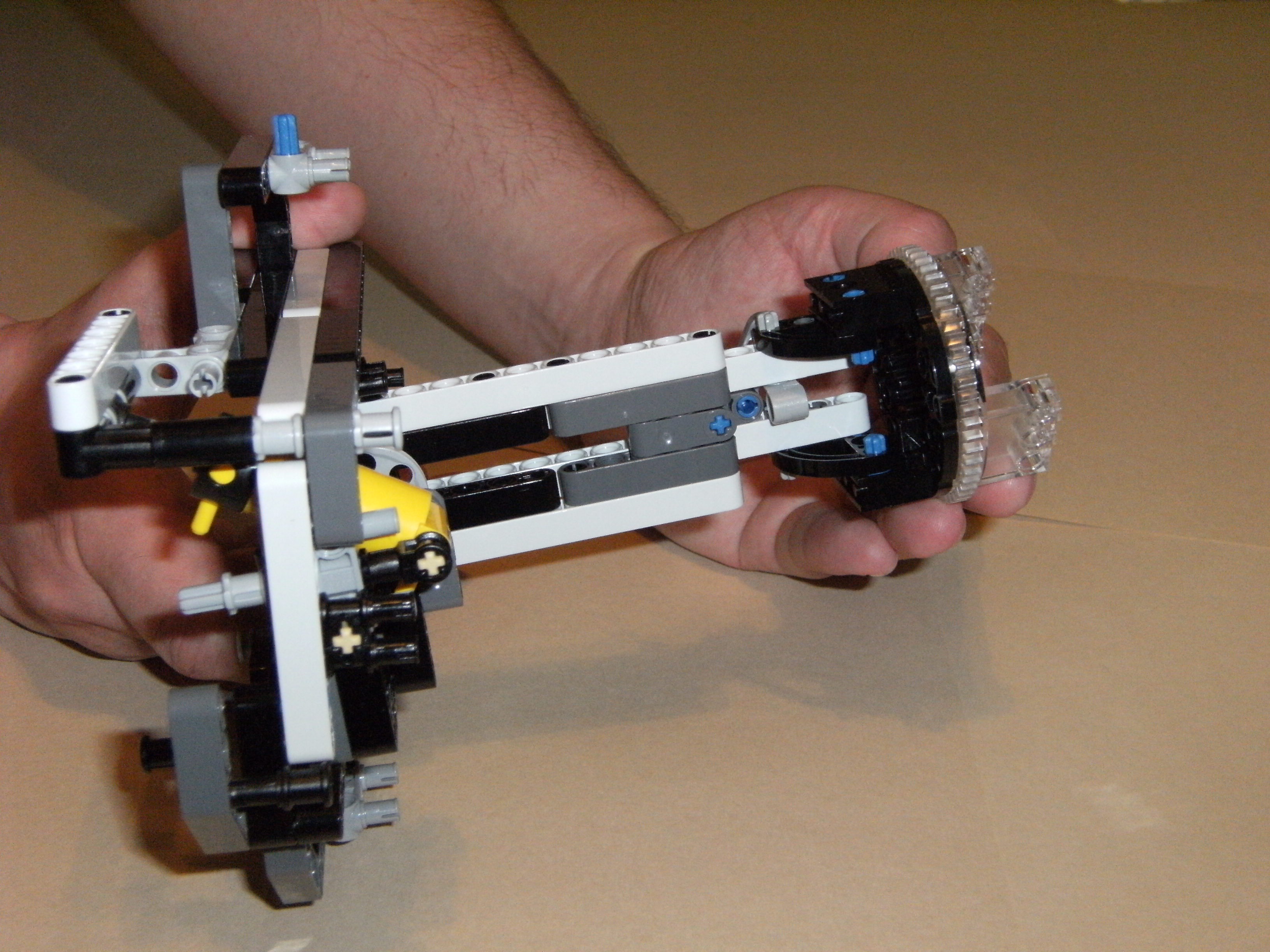

Figure 11. View 4 X-axis pivot

X-axis pivot

Figure 12. View 1 X-axis pivot

X-axis pivot

Figure 13. View 2 Y-axis pivot

Y-axis pivot

Figure 14. View 1 Y-axis pivot

Y-axis pivot

Figure 15. View 2 Y-axis pivot

Y-axis pivot

Figure 16. View 3 Y-axis pivot

Y-axis pivot

Figure 17. View 4 Telescoping

Telescoping

Figure 18. Leg extended Telescoping

Telescoping

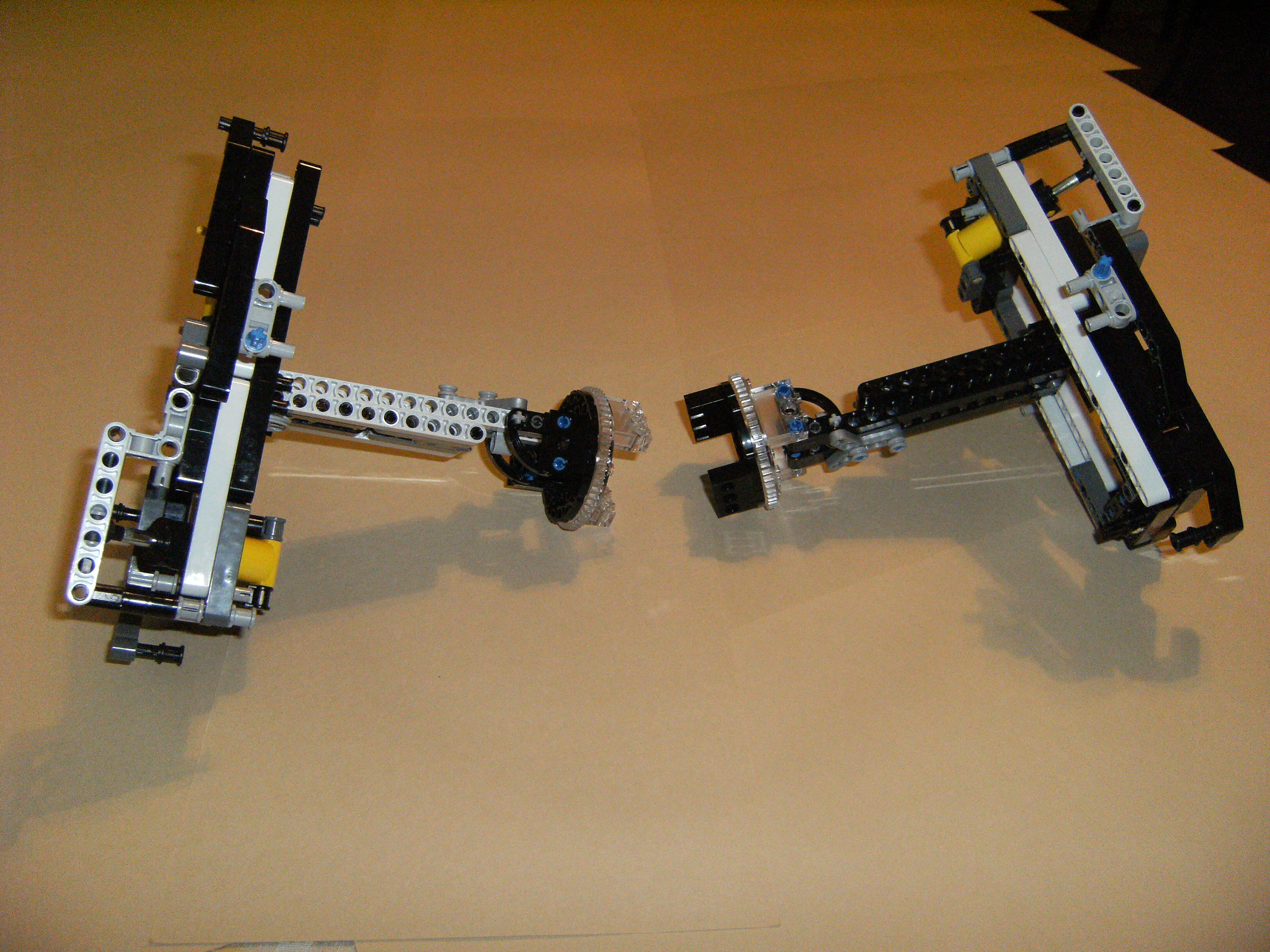

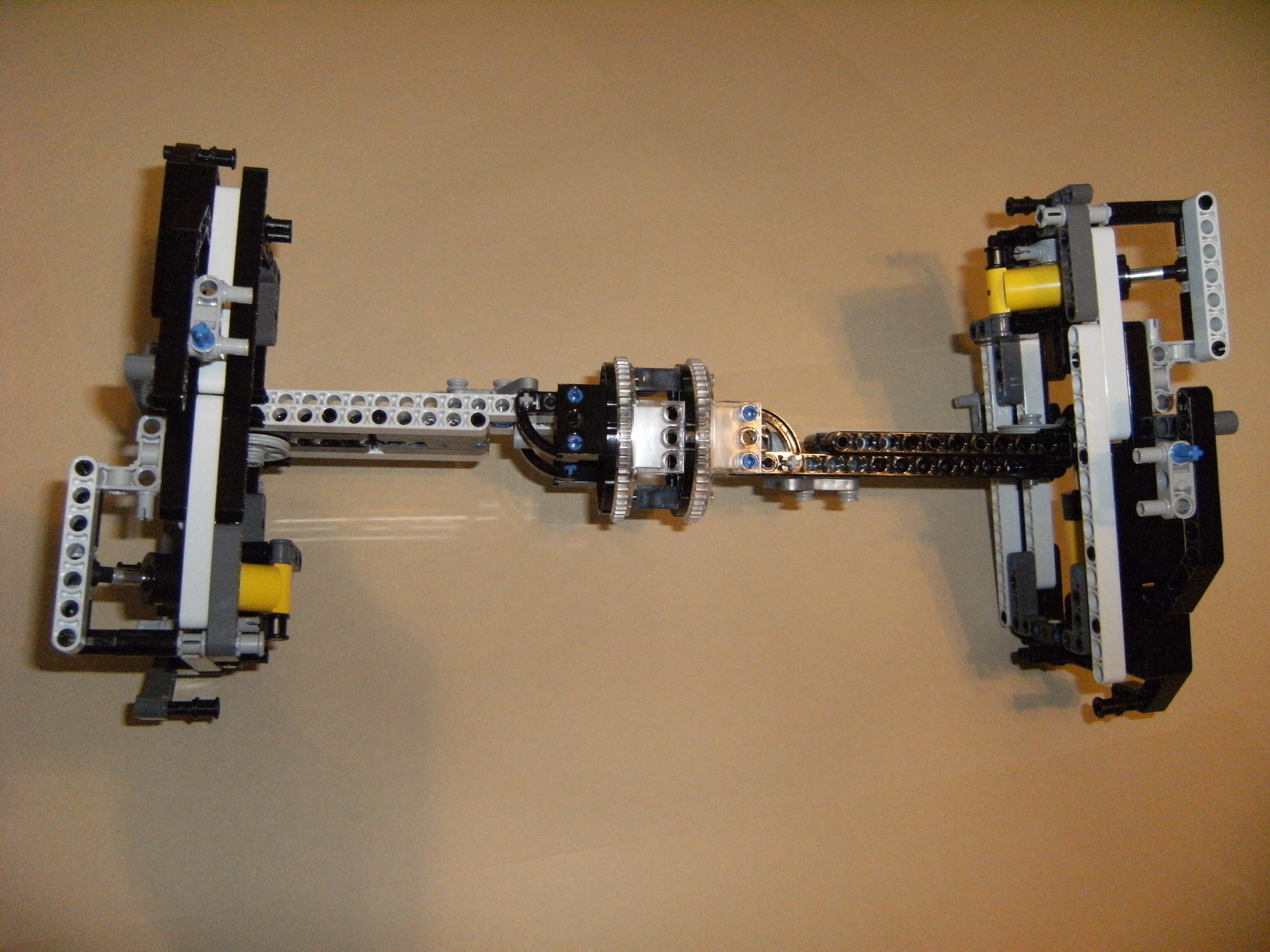

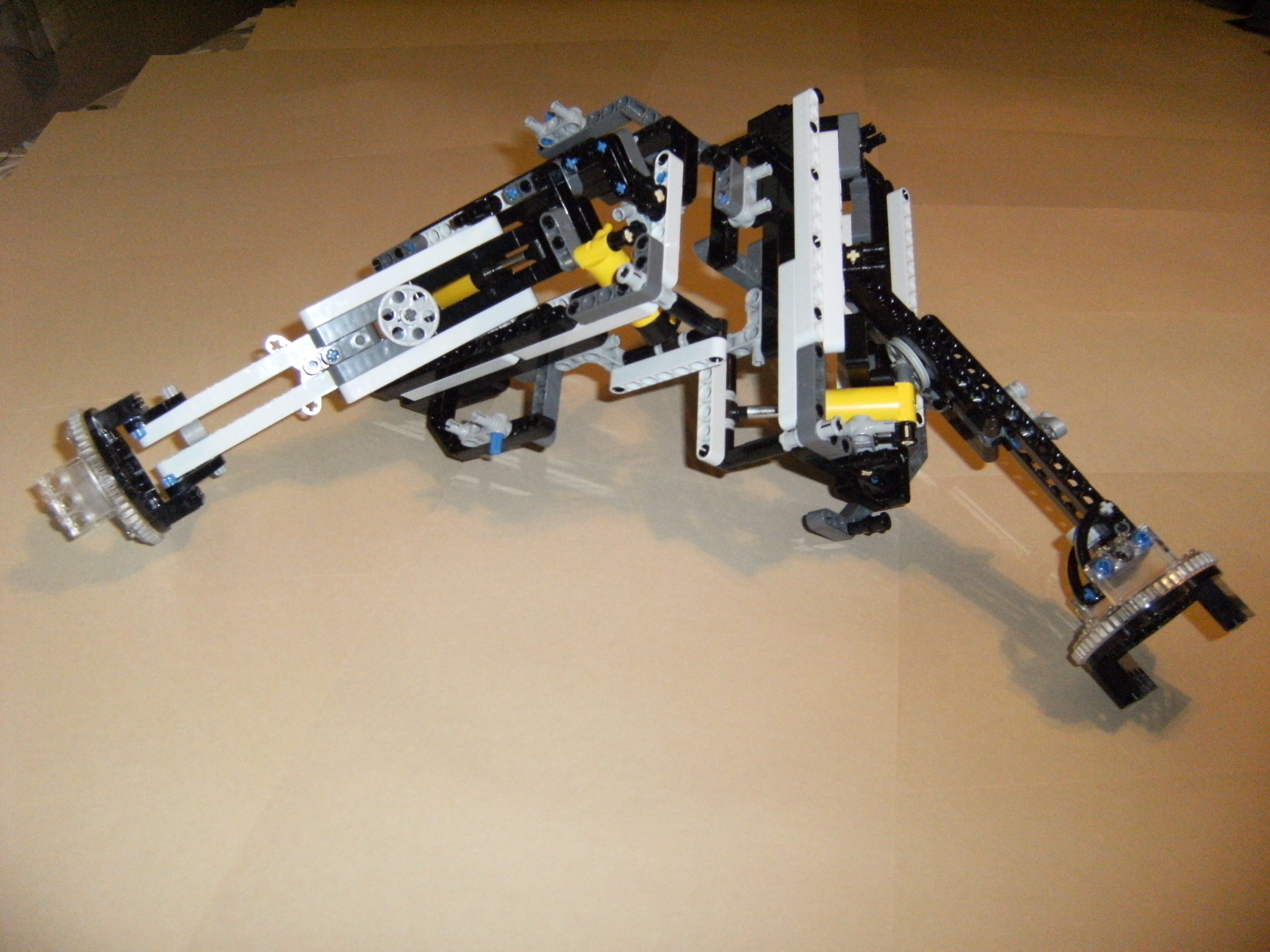

Figure 19. Leg retracted Two modules connected by telescoping shaft (connecting plates on legs)

Two modules connected by telescoping shaft (connecting plates on legs)

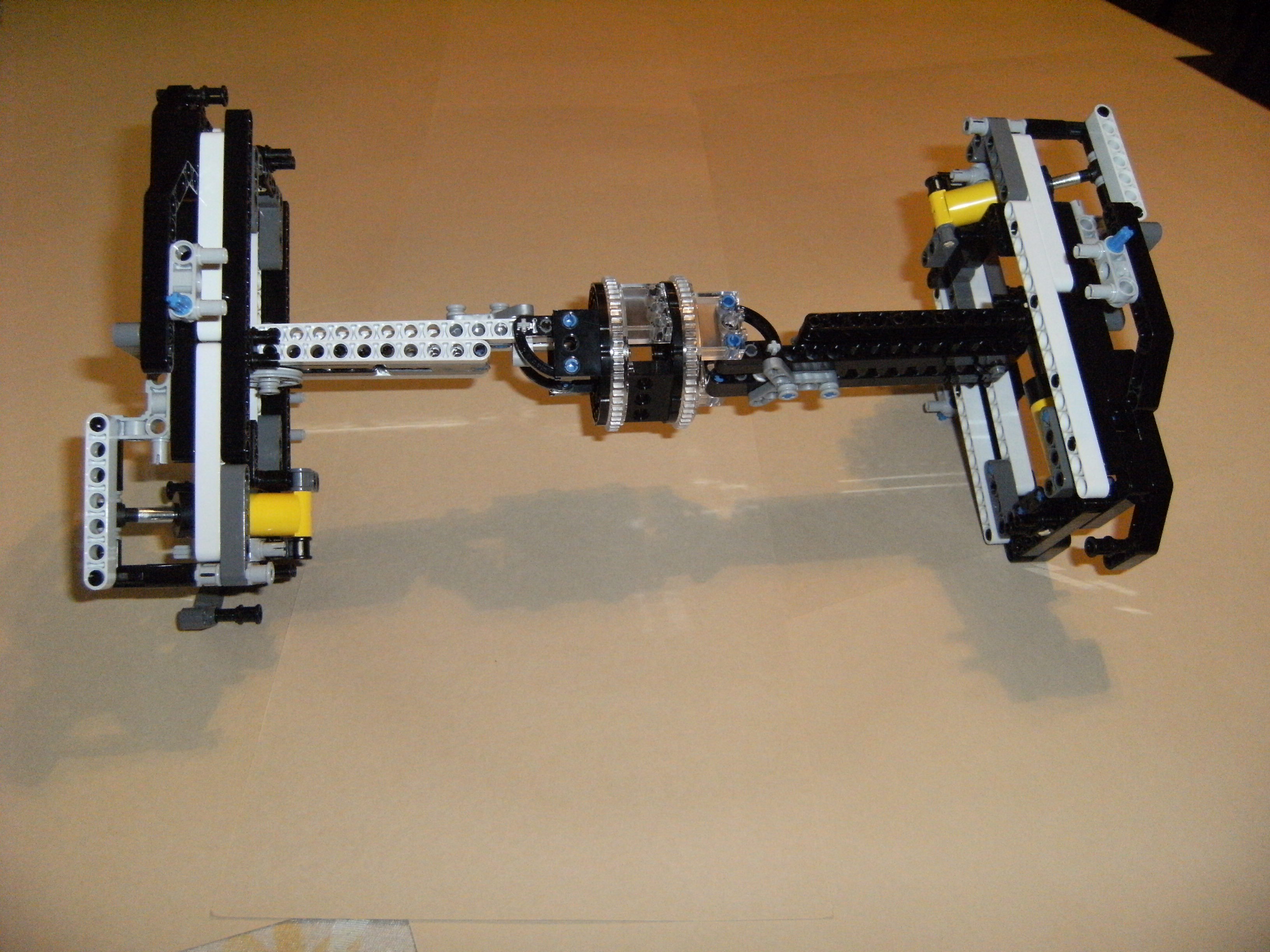

Figure 20. View 1 Two modules connected by telescoping shaft (connecting plates on legs)

Two modules connected by telescoping shaft (connecting plates on legs)

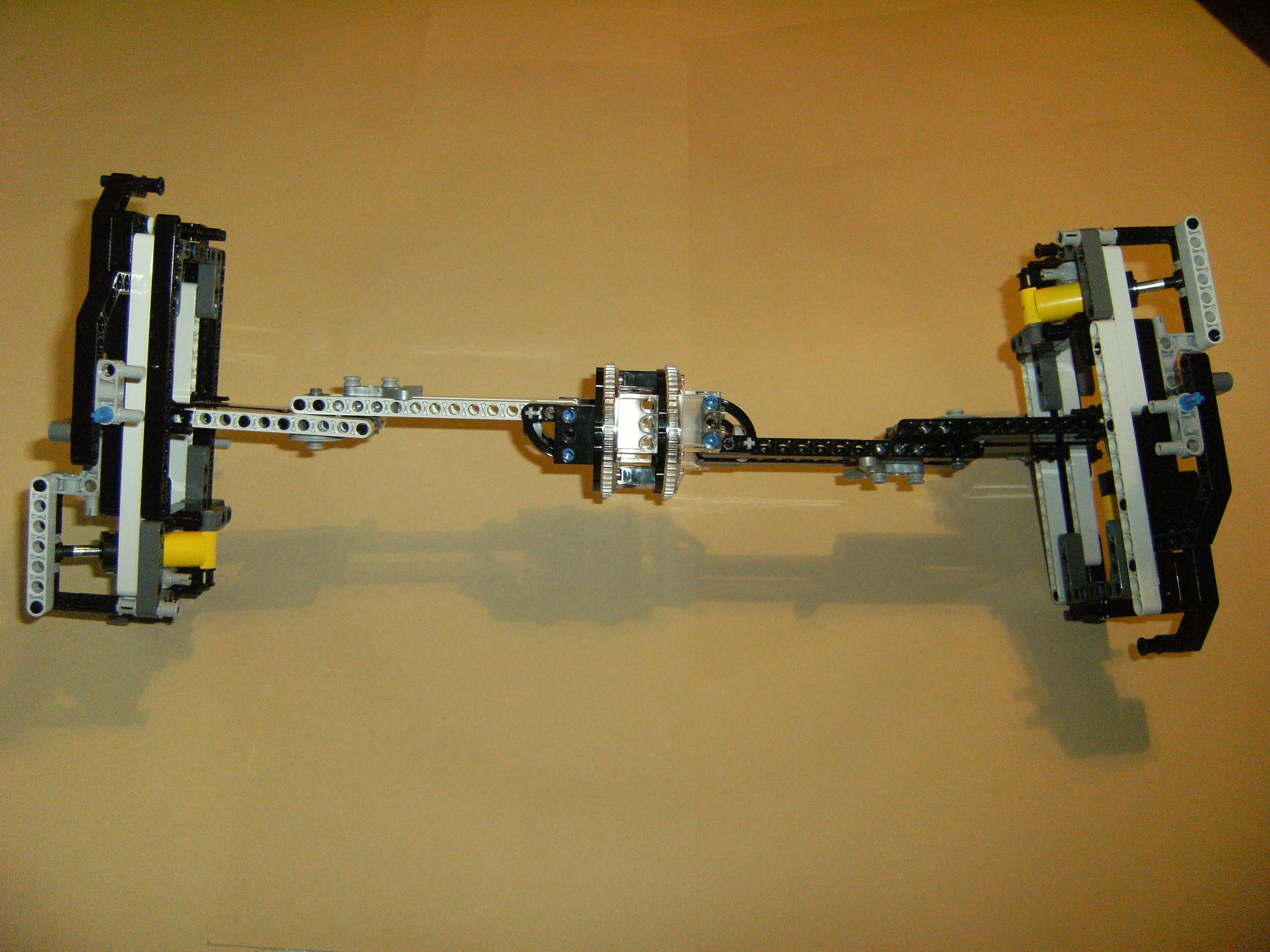

Figure 21. View 2 Two modules connected by telescoping shaft (connecting plates on legs)

Two modules connected by telescoping shaft (connecting plates on legs)

Figure 22. View 3 Two modules connected by telescoping shaft (connecting plates on legs)

Two modules connected by telescoping shaft (connecting plates on legs)

Figure 23. View 4 Two modules connected by telescoping shaft (connecting plates on legs)

Two modules connected by telescoping shaft (connecting plates on legs)

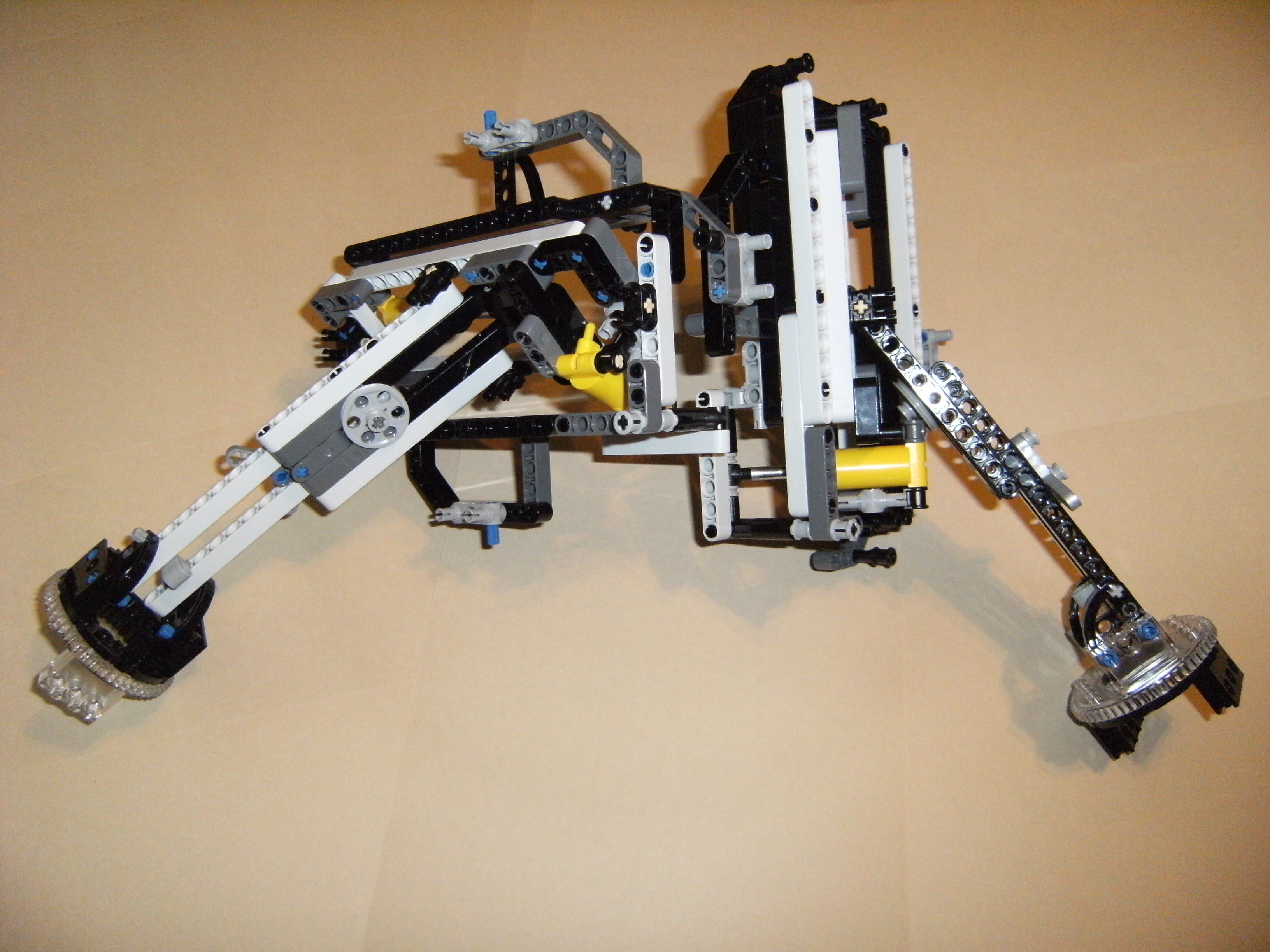

Figure 24. View 5 Two modules connected for partial cube faces

Two modules connected for partial cube faces

Figure 25. Side view Two modules connected for partial cube faces

Two modules connected for partial cube faces

Figure 26. Top view 1 Two modules connected for partial cube faces

Two modules connected for partial cube faces

Figure 27. Top view 2 Two modules connected for partial cube faces

Two modules connected for partial cube faces

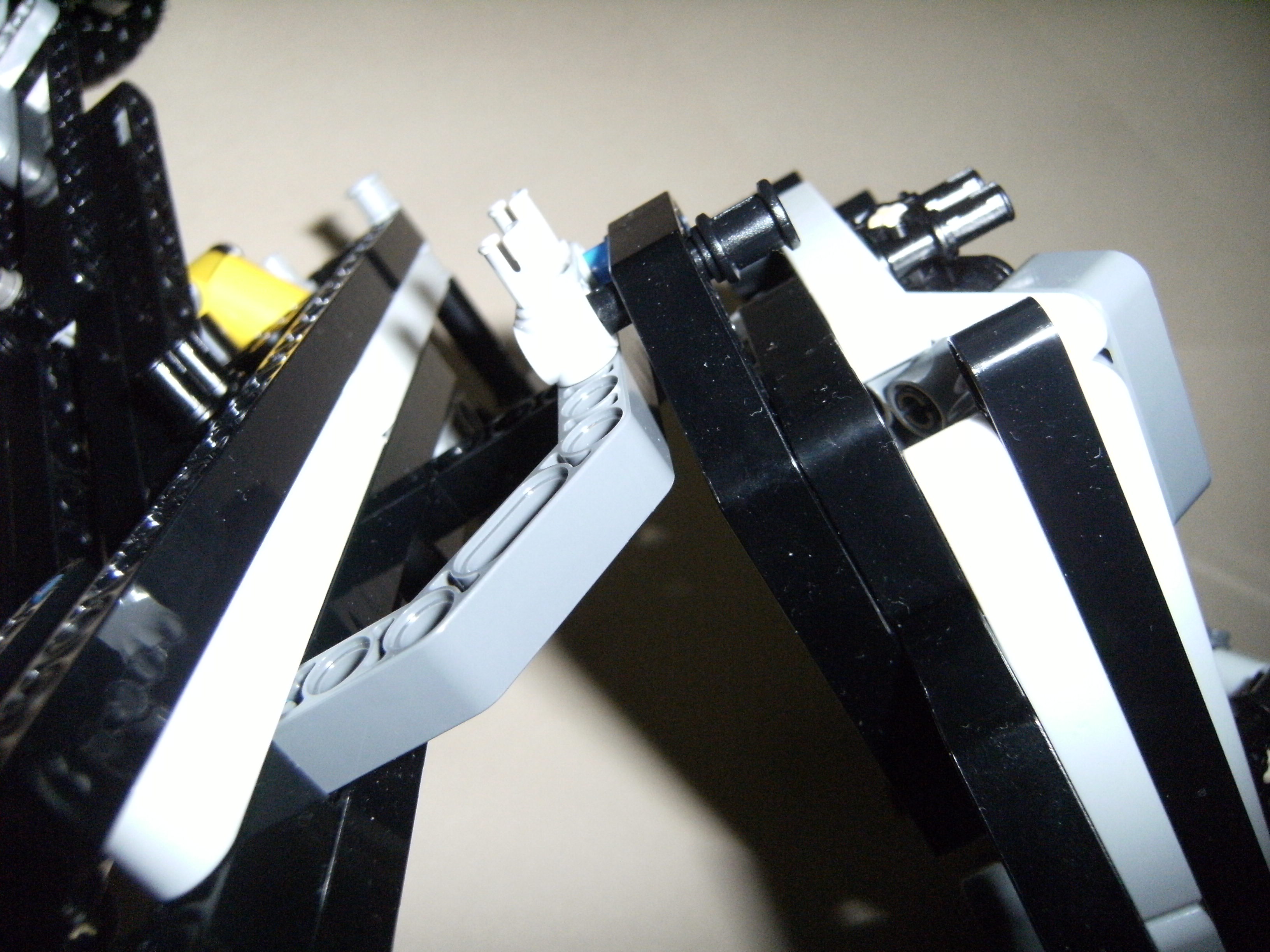

Figure 28. Link close-up